- Book Report

- Posts

- October report

October report

Eternal return edition

I was really on my never-ending math equation bs this month, by which I mean that I went all-in on dissociating from the world/my life by reading a lot of books that inspired me to think about time, the self, and novels.

What I read in October:

Rumaan Alam, Entitlement (2024)—Alllll the way back in Year 1 of the Report—the October 2020 Report, no less—I read and loved Alam’s class-skewering apocalyptic weekend getaway novel, Leave the World Behind (2020). I loved it, but not enough to follow Alam anywhere. That is, not enough to buy his next book in hardcover.

So here we are in 2025, with the recently published paperback of Entitlement, which follows the precariously middle class Brooke Orr as she navigates experiences typical to a certain kind of person in their early 30s—career pivots, friendships evolving and being tested by changes in material circumstances, and an ambient pressure to meet typical markers of success such as homeownership or marriage or major career advancement.

Across his oeuvre, Alam’s bread and butter has been his ability to dramatize, in precise detail, contemporary class distinctions and the elaborate codes that sustain them. In other words, he writes in the tradition of Austen, Dreiser, Wharton, and Fitzgerald, turning a surgical eye to the world of the wealthy and the beautiful little fools who strive to join the upper classes.

Where he really innovates is in the absolute dread he conjures in the reader as his narratives unfold. In Entitlement, he shows that he doesn’t need the framework of immediate global destruction to generate the pervasive, sickening sense that something bad is going to happen. From the start of the novel, when Brooke starts her new job at a new philanthropic enterprise founded by a billionaire seeking to give away his fortune, everything feels like a portent . . . but of what? And that question drives much of the narrative. There’s an almost menacing old-school German fairy tale aura that hovers around the pages, something about what Alam does and doesn’t show us about Brooke, especially as she begins to work closer with her billionaire boss. Of course I won’t tell you what bad thing happens, but I will tell you that to me it was both a bit baffling and also kind of agonizing, speaking as a reader capable of cosmic reserves of second-hand embarrassment.

Here’s the thing—after the challenging endeavor of A New New Me, I wasn’t fully ready for another highly formally experimental novel, eager as I was to read Patricia Lockwood’s newest book. I needed something conventional, for my brain. And because my brain loves a little mystery, is the kind of murine mind that loves to pull the lever for another pellet of dopamine, I read through Entitlement quickly, racing toward the end in the hope that I’d find something that would retroactively make the preceding pages take on a greater meaning than they had initially appeared to present.

But idk! I think Alam was trying to fit too much into this morality tale, and starting his story about the universally corrosive effects of capitalism with a protagonist who explicitly lacks a strong sense of self and values made it hard for me to get a grasp on this character’s significance and thus on the novel’s overall orientation. In a way, this novel read like a Reddit query whose answer is ESH (everyone sucks here), but I don’t think that was Alam’s goal, actually?

What I’m saying is, Entitlement was kind of giving “showstopper created by a GBBO contestant who got too lost in the sauce of style and totally ignored their ‘flavours’”—beautiful to look at (nice sentences), but tastes bad (diffuse critique)!!

I actually love an ominous atmosphere, but only if it resolves in a way that is satisfying to me.

Patricia Lockwood, Will There Ever Be Another You (2025)—I’ll eat one of my many baseball caps if any longtime readers of the Report remember that I read a galley of Lockwood’s first novel, No One Is Talking About This (2021), in the same month that I read Rumaan Alam’s Leave the World Behind. And little did I know as I was reading those books and writing about them for the very first October edition of my Book Report that Lockwood was already on the nightmarish Long COVID journey that would form the inspiration for her second novel, which I read this October. Time really is a flat circle, isn’t it?

Anyway, at risk of revealing far too much about myself,2 in terms of my favorite living authors under the age of 50, Lockwood is . . . up there, high in the top 5. I just KNOW Salieris abound in this world, seething with rage and admiration for her genius, for her direct line to a God I don’t believe in. I’m simply blessed to be able to read her writing. And especially so when I can understand it 🤪

An important thing to know about Lockwood is that she is a poet. Another important thing is that she’s online in a way that makes me wonder sometimes whether she didn’t invent certain parts of the internet, that’s how tuned in she is to the absurdity, language, and identity of The Internet. But it’s not just Online. It’s the whole lifetime of cultural references stored in her brain, and the way she calls them up, and the words she uses to talk about them and connect them to other references in service of larger ideas. I’m sure I wouldn’t love her as much as I do if I didn’t understand so many of her references (by virtue of being roughly the same age as her, and of having been a voracious consumer of books, television, and music in my childhood, and of reading some of the same Internet in my 20s that she was clearly also reading). I think that might be why I marvel at her talent—so many references are in the deep storage of my brain, chilling, but Lockwood conjures them up in her mind and makes them talk to other references, smashing disparate images together in a way that I’d never have imagined until she presents them, in all their logic.

But that’s what a poet does. A poet describes a woman screaming and vomiting in the hospital as sounding “like a gorilla, or the guy from Disturbed” (58), and readers who know what the guy from Disturbed sounds like know that there’s only one sound the poet can mean with this reference. A poet gives definition to words or concepts that are already defined, but the poet’s definition expands the concept or at least casts it in a new light that helps the reader see and understand something about it for the first time: “Fandom, which [she] had never understood, must be a way to organize life, longing, and a desire to look things up on the internet—three things that were too large otherwise” (151).

I’m not sharing even close to the best quotations here, partly because I sincerely don’t want to put any “spoilers” in this Report. Lockwood is so good at starting somewhere—you don’t even realize she’s starting—and taking the reader along, and then two pages later bringing it all back to the starting point, but this time with the previously random or innocent-seeming reference, line, or sentence now taking on a meaning that you could never have seen coming. Sometimes the meaning is just an insanely perfect pun about Roland Barthes. Sometimes it’s about the narrator’s nineteen-year-old niece being the living embodiment of Walter Benjamin’s/Paul Klee’s Angel of History. Other times the meaning is about how we communicate now in a world where algorithms, access to infinite information, and the erosion of consensus reality encourage the development of individual and totalizing subjective realities.

Anyway, this is a book about COVID, which happened and is still happening everywhere, “[t]o Ohio, even, she thought to herself, though we are not supposed to write about it” (25). And it is also a book about our young century and what it means to be alive and make art in this time. Idk I thought it was amazing. When I finished reading, I wondered: is this what people felt like in 1925 when they read Mrs. Dalloway for the first time????

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey (1817)3—Speaking of genius literature!!!

Do y’all know about Jane Austen?

This is the only book of hers I’ve read and now I’ve read it twice, lmao.

2025 is really shaping up to be a year where I return to books I last read nearly 20 years ago. As with Moby-Dick, I loved Northanger Abbey in college when I first read it. I can only guess as to why that love didn’t translate into me ever reading another Austen novel, but part of it might be the narrative I learned at the time, that Northanger Abbey is sOoOoO different from her other books. The first one Austen wrote (!), which she wrote when she was in her early 20s4 (!!), a perfect and loving send-up of the Gothic genre and the girlies who love reading fiction (!!!). If I loved this Austen novel, which is allegedly not like her others, then how could I possibly love the others? That was my thinking at the time, when I was a child.

As noted in the introduction to the Vintage Classics edition, Northanger Abbey “is very much a novel about novels” (ix), containing “some of the most passionate if sarcastic exegeses in praise of the novel ever to be tucked delicately into the pages of one” (xii). And I have to admit, Austen’s commentary on novels got me fired up (complimentary), like YES, JANE, a novel is “only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humor are conveyed to the world in the best chosen language” (27). Too true, my good woman.

Back when I was addicted to tiktok, the algorithm once decided I was the right demographic for videos about how to get into Berghain, which is maybe the funniest error an algorithm has ever made about me. This algorithmic “decision” caused me to read extensively about the famed Berlin nightclub, and to think about what goes into making a person who requires marathon, multi-day clubbing with the loudest possible music and the hardest drugs to feel satisfied. I imagine that many years of escalating club stakes, pursuing ever more novel ways of experiencing dancing to music, is what goes into such a person.

Reflecting on how deeply I enjoyed Will There Ever Be Another You, Northanger Abbey, and Heart the Lover (more on that below), I realize I can relate to the Berghain devotee. After reading so many novels in my lifetime, so many plots recounted in so many different styles and structures, it’s really the novels about novels that I enjoy the most. Having read it all,5 the only things left to truly enjoy are the novels that meditate on the process of their own creation and on their relationship to the “existing monuments [that] form an ideal order among themselves.” But don’t get it twisted—I also watched an insane amount of postseason baseball this month for The Narrative, and I will always love watching Sport for The Narrative.

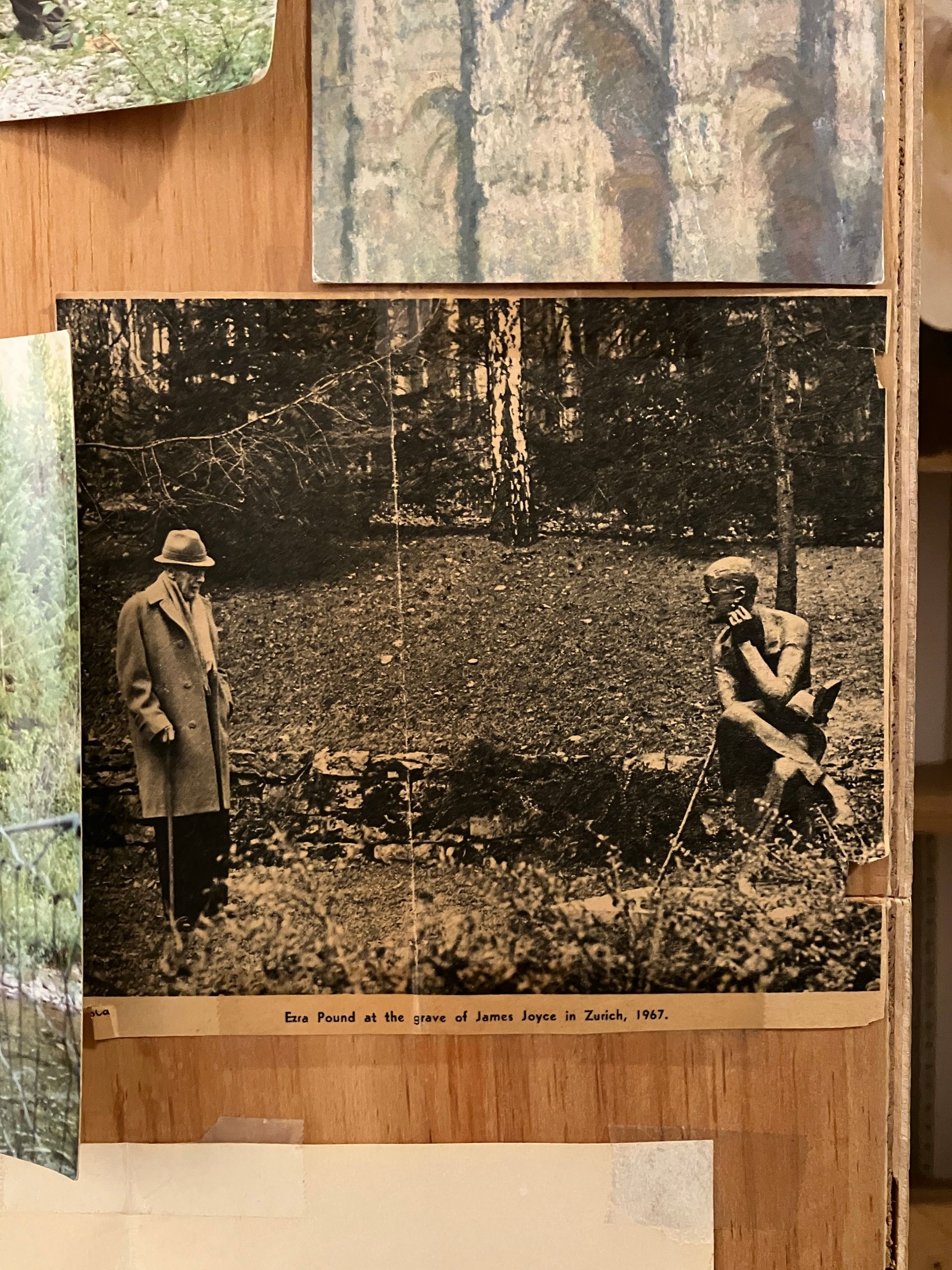

A couple of monuments on the wall at Unnameable Books.

Lily King, Heart the Lover (2025)—April Book Report, 2022, a mere 3.5 years ago when I read Lily King for the first time. What a revelation that was for me, what a treat.

Here she is again, with a stealth prequel to Writers & Lovers (2020), something I never would have dared to wish for and something that is so rare—a sequel that’s just as good as the book that preceded it—marred only slightly by some glaring typos that surely would never have made it to print if Grove Press cared enough to pay for serious copy editing.6

OK, now that I have my lone criticism out of the way, ahhhhhhh what a book!!! I stayed up until 1:00 in the morning on a school night to finish it and I would have stayed up even later if there had been more to read. But there wasn’t more to read because King is a masterful writer and she knew just how many pages she needed to tell this story. I confess, I read a library copy of Heart the Lover because I was scared that I might not love it enough to want a copy for my shelves. Shout out An Anonymous Donor, whose support enabled the Queens Public Library to purchase this book, but I am also going to be buying a copy of this book for myself, so that I can read it again whenever I want in the future.

Do you even need to know what Heart the Lover is about? imo you don’t, but I’ll tell you anyway. It’s about a woman in college, learning how to write fiction and learning about who she is and who she wants to be. There are boyfriends, there is a love story. 20 years elapse.7 Events occur that bring her back to the people she knew in her college days, some of whom she hasn’t seen or talked to in the previous 2 decades. Life happens, has happened, is happening to her. It’s just like what Tolstoy says in Anna Karenina (1878), as Lockwood’s narrator in Will There Ever Be Another You quotes, “Karenin was being confronted with life . . . and this seemed stupid and incomprehensible to him, because it was life itself” (100). Except, because Heart the Lover is a künstlerroman, its protagonist is at least able to make some parts of her life comprehensible, to herself and to the reader, and the result is simply an exceptional novel.

Foster Report: We call him Mr. Charles because we don’t like his shelter name (“Chuckle”).

Emily Nemens, Clutch (February 2026)—I concluded my October with a galley copy of Emily Nemens’s second novel, which is about five friends and the lives they’ve led in the 20-odd years since they first met in college. Appropriately, I received this galley from Carissa, who has been a Friend of the Report’s Author (aka me) for even longer than the women in this book have been friends!

I guess this month was as good as any other for me to ponder the nature of time and its passage, and I enjoyed the coincidence of following Lily King’s fictional look into the somewhat recent past with Nemens’s approach to structuring a novel around a roughly 20-year gap. I also enjoyed that Nemens anchored her narrative around women’s friendships and her loving depiction of the power of such relationships, however tenuous they may sometimes feel when individuals are careening from one day to the next, trying to “have it all.”

Nemens covers a lot of ground in Clutch—by essentially having 5 main characters, she is able to explore that many more experiences, questions, and conflicts an individual might experience on their own or via their loved ones. Ambition, addiction, art, love, loss, childbirth and rearing. Seen from one angle, Clutch is a classic mid-life crisis novel, where all of its characters at one point or another find themselves looking up from their daily grind and wondering what their purpose is, why they’ve been working the way they have, what the next 40 years will hold, and how do they feel about this trajectory?

Seen from another angle, Clutch is not unlike the first book I read this month (Entitlement) in that it’s an intelligent and accessible novel that explores concepts of agency under late/finance capitalism. A certain type of reader might ask what is the goal of humanizing a woman born into wealth who chooses to make her living in orchestrating and carrying out mass layoffs? Or of giving depth and complexity to a woman who marries an Elon Musk-type man? They would be valid questions! But for a novel that in many ways represents a present-day reboot of Mary McCarthy’s The Group (1963), it makes sense to have these kinds of characters (among several others), who are needed for their symbolic value of representing the structural forces that shape individual lives. Nemens depicts various early steps along the path of awakening consciousness of gender and class, offering examples to a specific kind of woman who might be likely to read this novel. That I personally may not belong to that audience doesn’t mean I couldn’t find much to appreciate about this book. But Clutch also inspired me to want something a little less . . . careful . . . for my next read.

What I’m looking forward to reading in November:

Bernardine Evaristo, Girl, Woman, Other (2019)8

Arundhati Roy, Mother Mary Comes to Me (2025)

Susan Orlean, The Library Book (2018)

1 Pronounced: flayyyvahhhs.

2 lmao!! That’s all I do in this book blog!!

3 Book Club selection for October.

4 She sold the manuscript in 1803 to a publisher who ended up changing their mind. It was finally published a few months after she died, in 1817.

5 I do not pretend for one minute that I’ve read it all. I’m taking a little blogger’s artistic license here.

6 “Warrantee” (91) was jarring. The British English “judgement” (93, 220) was concerning. “Finnegan’s Wake” (15, 203)—emphasis on that apostrophe—in a book about English majors and writers, was appalling.

8 Book Club selection for November.